The Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum has announced the acquisition of a private letter of historical importance written by Dr Samuel Johnson, confirming it will remain in the UK for public display.

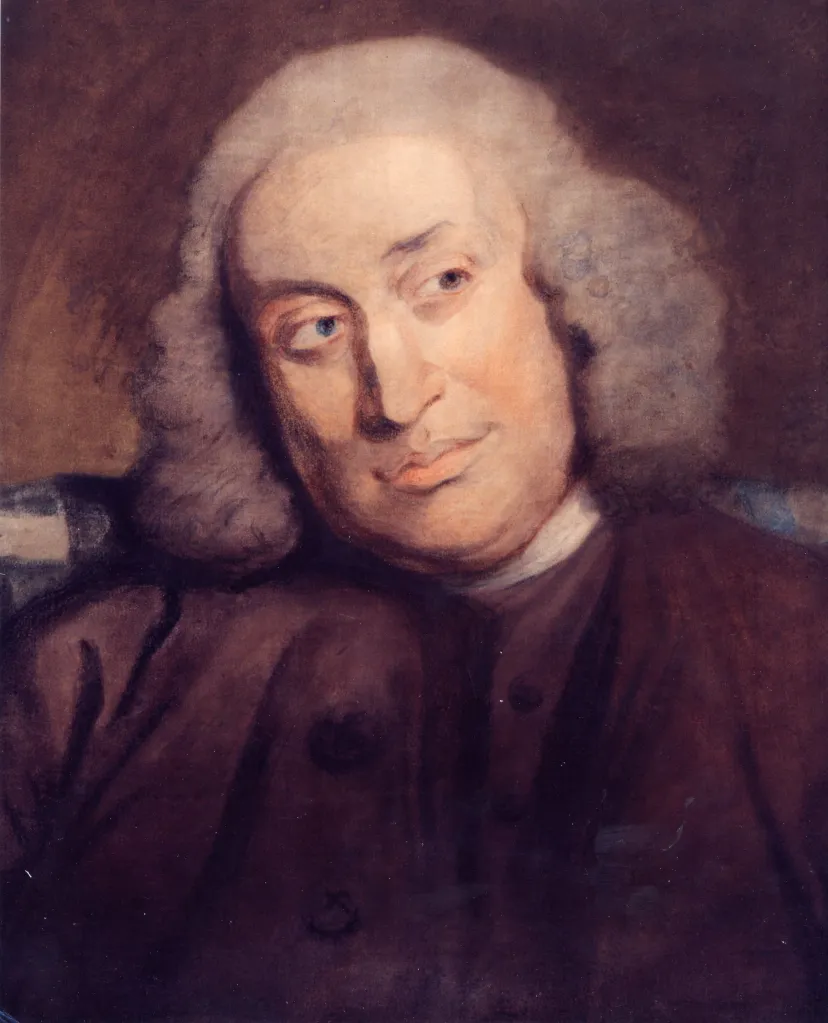

Born in Lichfield and best known as the author of A Dictionary of the English Language in 1755, Samuel Johnson was also a playwright, poet, journalist, editor, and biographer, and is highly regarded as one of the 18th century’s most important men of letters.

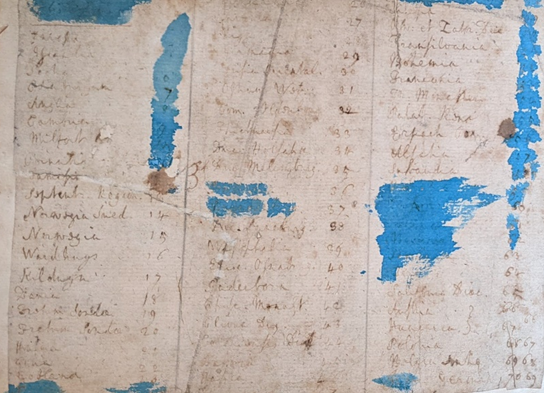

The letter, penned by Johnson in 1783, had been documented but its location was unknown, and scholars thought it was lost. After 240 years it was discovered in a cupboard amongst other historical letters in a Gloucestershire country home and was sold at auction on the 19th of September. It is addressed to a twelve-year-old Sophia Thrale, daughter of Hester Lynch Thrale, a British author and patron of the arts. Samuel Johnson regularly corresponded with Hester Lynch Thrale and her children, and these letters became of historical significance, providing great insight into Johnson’s mind and a resource for the study of 18th century society.

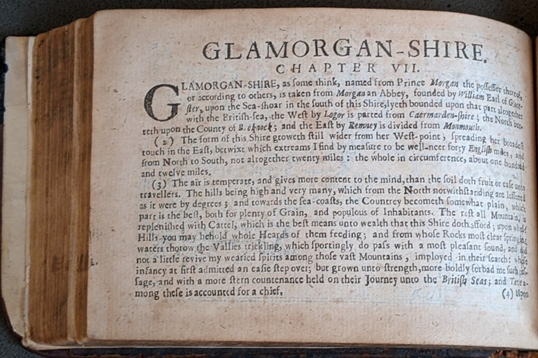

In the letter we read Johnson encouraging Sophia to continue her studies, especially her mathematical pursuits. It demonstrates his enlightened views on the importance of women’s education in the eighteenth century, and the openness he had towards young people in general. This charming correspondence is a rare and documented example of a different side to Johnson, its affectionate and paternal tone shows a softness not often associated with him. It also provides further evidence of Johnson’s interest in mathematics during his later life, not a field he is not known for.

Plans are underway for the letter to go on public display in The Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum in Lichfield. This free museum welcomes visitors throughout the year and was once the family home where Johnson spent the first 27 years of his life.

The acquisition was made possible by funding and support from the Friends of the National Libraries, The Johnson Society (Lichfield), Lichfield City Council, and the generosity of Phil Jones, a private donor.

Friends of the National Libraries, founded in 1931, are dedicated to saving our written and printed heritage through awarding acquisition grants to national and regional archives, libraries, and collections.

Nell Hoare MBE, Friends of the National Libraries, said:

‘What a terrific achievement! Trustees of Friends of the National Libraries’ (FNL) were impressed that Samuel Johnson’s Birthplace Museum secured such significant local support at short notice to raise sufficient funds for success at auction against stiff international competition. We are delighted to have played a part bringing Johnson’s recently re-discovered letter to Sophia Thrale into the museum’s collections, where it will be accessible to all in perpetuity.’

The Johnson Society, founded in Lichfield in 1910, encourages interest in the writings, life, and times of Samuel Johnson, and has remained constant supporters of The Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum.

Phil Jones, Chairman of the Johnson Society, said:

“We are delighted that the Birthplace has been able to secure this important and historic letter, written in Johnson’s own hand, against fierce competition. The Johnson Society has worked closely with the Birthplace and others to make this happen. It is wonderful that a historic artefact has been retained for local people and visitors alike to enjoy. It demonstrates the ongoing relevance of Johnson and his writing for a contemporary audience.”

The Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum is operated by Lichfield City Council.

Councillor Dave Robertson, Lichfield City Council, said:

“Our shared history and heritage should belong to all of us and thanks to the excellent work of our officers, alongside the Friends of the National Libraries, Johnson Society and private individuals. I’m so pleased that the City Council has been able to make sure that this important document stays in the UK and in the hands of the public.”

Councillor Ann Hughes – Mayor of Lichfield, said:

“Wow! I am absolutely delighted that with very generous donations from the Johnson Society, Friends of the National Libraries, Phil Jones, and the help of Lichfield City Council this long-lost letter from Samuel Johnson has been secured for the city. Well done to Kimberley Biddle, our new Museums and Heritage Officer for bringing everyone together to make it happen.”